- About

- Contact

- Blog

- CONSUME

- GALLERY

-

PERAMBULATIONS, Etc.

- Old Parcels Office, Scarborough

- Ghent

- White Cube

- Cornerhouse, Manchester

- Venice 2019

- Tectonics

- Leeds City Art Gallery

- Hayward Gallery, London

- Hull University Art Gallery

- Whitney Gallery, New York

- Royal Scottish Academy, Edinburgh

- Talbot Rice Gallery, Edinburgh

- Fruitmarket Gallery, Edinburgh

- Modern One & Two, Edinburgh

- Groeningemuseum, Bruges

- Humber Street Gallery, Hull

- Renwick Gallery, Washington DC

- Arenthuis, Bruges

- Ropewalk Gallery, Barton on Humber

- Geementmuseum, Den Haag

- Ferens, Hull

- Crescent Arts, Scarborough

- Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool

- Hepworth Wakefield

- Yorkshire Sculpture Park

- Stedelijk, Amsterdam

- Henry Moore Institute

- Louisiana

- SMK Copenhagen

- Yorkshire Sculpture International

- Tate Modern

- Whitworth, Manchester

|

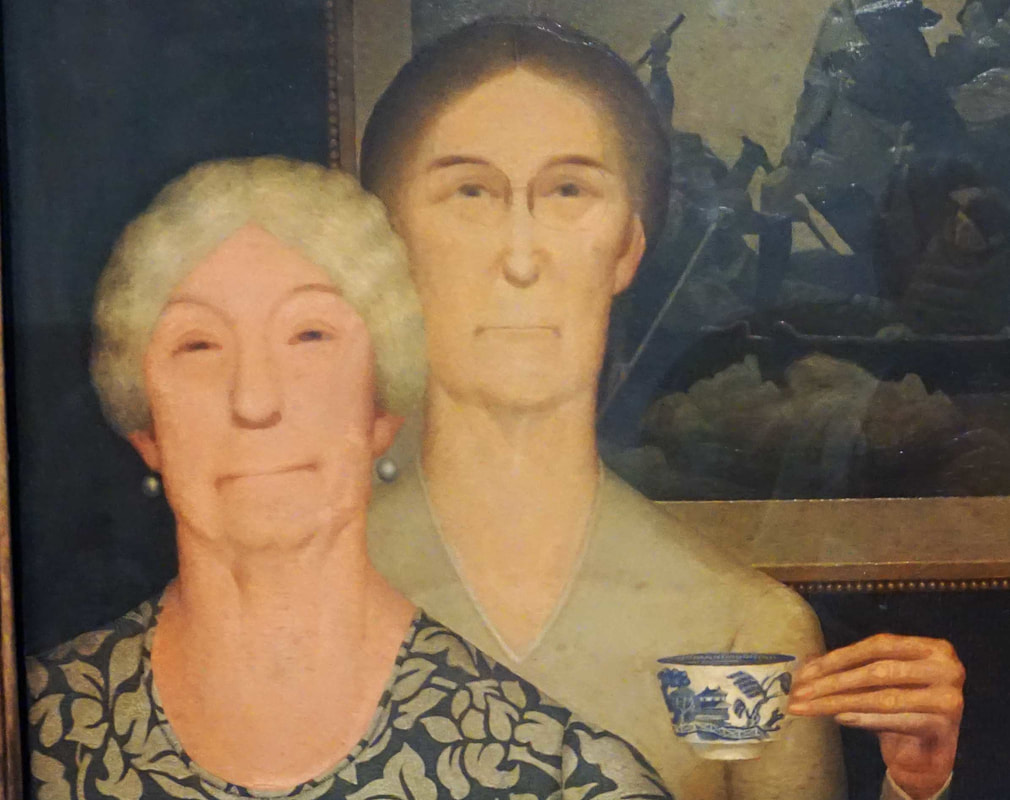

Grant Wood: American Gothic and Other Fables, to June 10th 2018

Grant Wood’s best known picture – American Gothic (1930) portrays a couple of rural folk staring unblinkingly straight into the camera (so to speak, this is of course a painting but is semi-photographic in its mastery of detail). The woman looks a little disdainful, the man clenches his pitchfork, upright – a sentry in defence of his homestead, his wife’s virtue, his pile of straw – who knows? Many pundits have commented on the mystery of this picture, but perhaps it is just a non-existent mystery of the blandness of austere rural life, a life captured in all its rustic po-facedness. The Grant Wood exhibition is nicely timed to coincide with a time when ‘rustic’ values - of thrift, homeliness, mythic struggles, patriotism and nostalgia have been revivified by the Great Trumpbobulation. Since we live in a period when aesthetic values appear to have flown out of the window in fear of the great god falsehood, maybe Wood’s 1930s superficially idealised world reconnects its American audience to an innocent place in their imagination, like in the UK we might gaze upon images which seem to capture an unreal if other worldly ‘Olde England’ (Ravillious, perhaps?) Wood’s vision was no reflection of reality when he painted and drew it – and boy, his drawings are as marvellous as his paintings – but his finesse of this vision draws the observer into a conflicted land of yearning for honest, down to earth earthiness. What a curious situation. The incumbent in the White House has a limited vocabulary – words like ‘beautiful’ and ‘beautiful’ and possibly an occasional ‘bad’ illustrate his command of at least one word with more than two syllables as well as one which only has one. Crucially, he rarely smiles and so were he not a product of the urban jungle, he could perhaps have featured in one of Wood’s pictures. (albeit not showering naked after a hard day’s harvesting in the baking heat of the mid-West ‘Ole America,’ one of Wood’s pictures that offended the US postal service). I mentioned here how little Trump smiles, and it is perhaps a significant feature of Wood’s portraits that his figures rarely smile. The dream world they inhabit is one of hard graft (a word Trump would understand in a different sense) and thrift (a word he certainly wouldn’t understand). Deciding on a search for smiles in this exhibition I first came across ‘Daughters of Revolution’ (1932). These elderly daughters meet their viewer’s gaze disapprovingly, suggesting perhaps that they have something quite nasty in mind. Only one of them appears to smile but her thin lips are pursed as if about to release a frozen drizzle of dry ice. The noses of these revolutionary daughters could each compete with an arctic pole or two. There is no humour in any of their facial expressions. Two hours drinking tea with them would freeze an Innuit. But yes, one of them has what passes for a smile. Chilling. Two women in ‘Appraisal’ (1931) might be in a discussion about the value of a hen, which the (much) younger of the two seems to be clutching perhaps with no intention of selling. Perhaps she’s smiling because she’s got the better of the older woman. Or perhaps it’s because she’s just bought the bird at a bargain price – having gained the advantage of the older woman. But then of course, maybe they’re both friends just doing a friendly deal. Somehow, in the context of the few other smiles on display in this exhibition, I suspect there’s something more to it than that. Here’s another ambiguity. ‘The Good Influence’ (1936) shows a woman dressed in black, outside a church. She fills the picture, there are no others portrayed here, so we are left to imagine why she would be alone, wearing black – and smiling outside a church. She’s either on her way or has just come from a funeral, and one feels bound to think it was her husband’s. No wonder she’s smiling, she’s seen the last of the old git after years of gnawing marital imprisonment. Perhaps the happiest looking smile, i.e. one which may really have a happy connotation is the woman’s apparently joyful visage in ‘The Practical Idealist’ (1936). But given the few, ambiguous smiles seen in Wood’s other work, what should we make of this? I suspect Wood chose his titles with care, and although there’s nothing in the picture itself to suggest that ‘idealism’ here means ‘wishful thinking’ could it be that the word ‘practical’ in the title is meant to be ironic and anything but practical? Lastly, in one of the final pictures in this comprehensive exhibition of Wood’s oeuvre, we come across a picture – a study for ‘In the Spring’ (1939) – of a man who is also very definitely smiling. He leans on his shovel in front of a field which one assumes he has dug over all by himself – or is about to - his smile might therefore be one of self-satisfaction. But he has no eyes, just dark recesses under his hat. There is even here something not quite right. There is no light in his eyes to match his broad smile. The devil smiles too. So, far from conjuring up an innocent image of ‘Ole America’ there is something sinister running through Wood’s pictures in this exhibition. What may at first sight seem a celebration of ‘good ‘ole times gone by’ may really be a negative portrayal of a mythic vision of the so-called blessed land where the devil is always just round the corner. I’m obviously not a Grant Wood expert, and merely offer these thoughts in the context of seeing his work close up for the first time. But I think the sometimes disturbing quality of his work has a very strong resonance today. An old American Satan is here now and perhaps we need a modern day Grant Wood to capture the sheer strangeness of that. Perhaps there is a modern day Grant Wood. It would be wonderful if one with his talent could step forward. |