- About

- Contact

- Blog

- CONSUME

- GALLERY

-

PERAMBULATIONS, Etc.

- Old Parcels Office, Scarborough

- Ghent

- White Cube

- Cornerhouse, Manchester

- Venice 2019

- Tectonics

- Leeds City Art Gallery

- Hayward Gallery, London

- Hull University Art Gallery

- Whitney Gallery, New York

- Royal Scottish Academy, Edinburgh

- Talbot Rice Gallery, Edinburgh

- Fruitmarket Gallery, Edinburgh

- Modern One & Two, Edinburgh

- Groeningemuseum, Bruges

- Humber Street Gallery, Hull

- Renwick Gallery, Washington DC

- Arenthuis, Bruges

- Ropewalk Gallery, Barton on Humber

- Geementmuseum, Den Haag

- Ferens, Hull

- Crescent Arts, Scarborough

- Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool

- Hepworth Wakefield

- Yorkshire Sculpture Park

- Stedelijk, Amsterdam

- Henry Moore Institute

- Louisiana

- SMK Copenhagen

- Yorkshire Sculpture International

- Tate Modern

- Whitworth, Manchester

Glen Onwin, from 1st February 2019

Leeds City Art Gallery

Here’s some key words: salt, edge, evaporation, tide, marsh, barren, monochrome. There you have it, a complete review of Onwin’s show at Leeds City Art Gallery. But of course there’s more to it than that. Onwin, whom I’ve never come across before, speaks a minimalist language, or at least he did in the 1970s when most of this stuff dates from. There’s a combination of photography, structures and paintings although in the latter case the materials used aren’t necessarily paints as such. Onwin’s show is presented as a counterpoint to a room full of Leonardo da Vinci drawingas nearby – part of the 12 site exhibition drawn from the royal collection. (Does this explain why the Queen always wears white gloves – cos’ she’s always leafing through her Leonardos?)

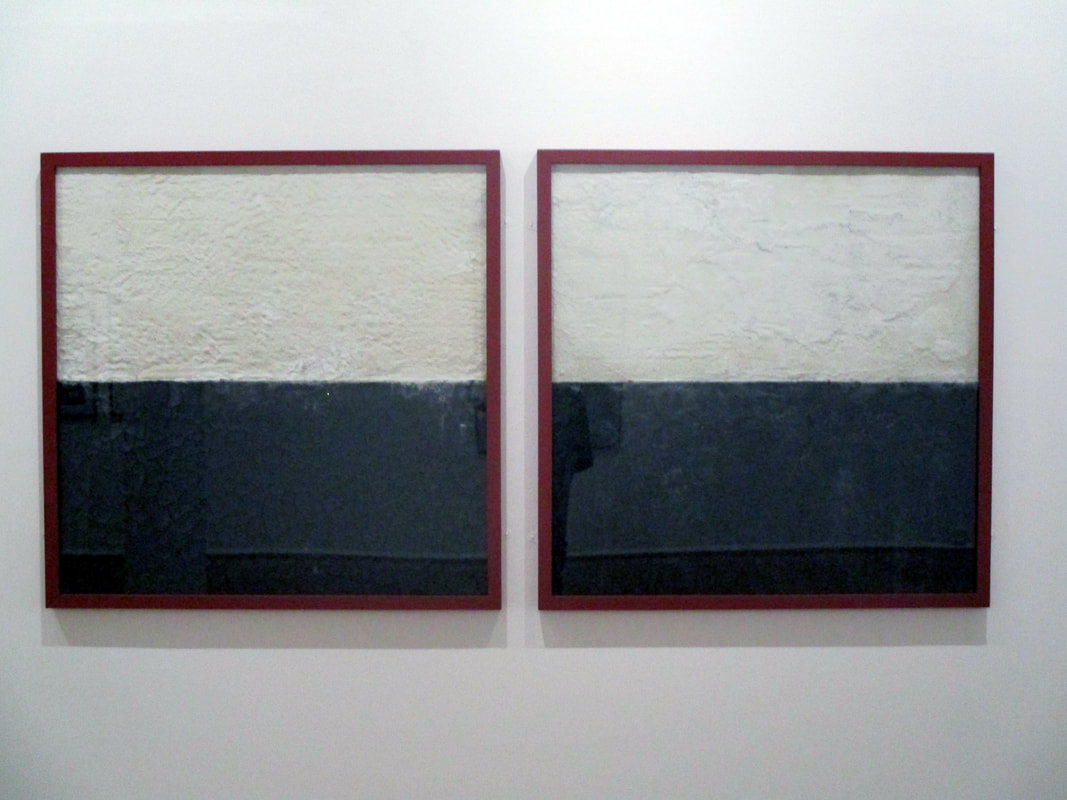

As the two pictures illustrated here demonstrate there doesn’t appear to be much going on. But this is deceptive, since the surface is heavily pitted and cracked, the lower half, dark and dried out could be the cracked mud of an estuary bank at low tide, the sky is salt laden, rough and brooding, even though it is light. This is landscape/seascape on the edge, where life struggles with the elements but also finds its appetite. Salt is the common theme of the works displayed here, Onwin has found his imagery in the barren wasteland that is Saltmarsh (somewhere down south I believe, but denizens of Humberside wouldn’t have to travel far for similar views) and here salt is harvested from the sea in what must be the way it was since medieval times. A couple of structures reminded me of Joseph Beuys’ attention to material – a cube of salt in a wooden box lies on the floor with long wooden ligaments attached almost as if it could be a plough, or rather a seed drill, ready to distribute its essential, elemental content on a metaphorical land.

Apart from the appearance of an occasional wooden structure, there is little evidence of human interaction with the flat horizons here. But our need for salt, a necessary ingredient of life is suggested all around even in our absence, even here in this bleak unwelcoming vista we are harvesting a commodity, perhaps in the same location as did the Romans. In this sense Onwin has delved into history as well as landscape, and it is a classic case of less is more – where the imagination can roam without limit. That is the allure of the space the artist probes on the border between the marsh and the sea.

Leeds City Art Gallery

Here’s some key words: salt, edge, evaporation, tide, marsh, barren, monochrome. There you have it, a complete review of Onwin’s show at Leeds City Art Gallery. But of course there’s more to it than that. Onwin, whom I’ve never come across before, speaks a minimalist language, or at least he did in the 1970s when most of this stuff dates from. There’s a combination of photography, structures and paintings although in the latter case the materials used aren’t necessarily paints as such. Onwin’s show is presented as a counterpoint to a room full of Leonardo da Vinci drawingas nearby – part of the 12 site exhibition drawn from the royal collection. (Does this explain why the Queen always wears white gloves – cos’ she’s always leafing through her Leonardos?)

As the two pictures illustrated here demonstrate there doesn’t appear to be much going on. But this is deceptive, since the surface is heavily pitted and cracked, the lower half, dark and dried out could be the cracked mud of an estuary bank at low tide, the sky is salt laden, rough and brooding, even though it is light. This is landscape/seascape on the edge, where life struggles with the elements but also finds its appetite. Salt is the common theme of the works displayed here, Onwin has found his imagery in the barren wasteland that is Saltmarsh (somewhere down south I believe, but denizens of Humberside wouldn’t have to travel far for similar views) and here salt is harvested from the sea in what must be the way it was since medieval times. A couple of structures reminded me of Joseph Beuys’ attention to material – a cube of salt in a wooden box lies on the floor with long wooden ligaments attached almost as if it could be a plough, or rather a seed drill, ready to distribute its essential, elemental content on a metaphorical land.

Apart from the appearance of an occasional wooden structure, there is little evidence of human interaction with the flat horizons here. But our need for salt, a necessary ingredient of life is suggested all around even in our absence, even here in this bleak unwelcoming vista we are harvesting a commodity, perhaps in the same location as did the Romans. In this sense Onwin has delved into history as well as landscape, and it is a classic case of less is more – where the imagination can roam without limit. That is the allure of the space the artist probes on the border between the marsh and the sea.