- About

- Contact

- Blog

- CONSUME

- GALLERY

-

PERAMBULATIONS, Etc.

- Old Parcels Office, Scarborough

- Ghent

- White Cube

- Cornerhouse, Manchester

- Venice 2019

- Tectonics

- Leeds City Art Gallery

- Hayward Gallery, London

- Hull University Art Gallery

- Whitney Gallery, New York

- Royal Scottish Academy, Edinburgh

- Talbot Rice Gallery, Edinburgh

- Fruitmarket Gallery, Edinburgh

- Modern One & Two, Edinburgh

- Groeningemuseum, Bruges

- Humber Street Gallery, Hull

- Renwick Gallery, Washington DC

- Arenthuis, Bruges

- Ropewalk Gallery, Barton on Humber

- Geementmuseum, Den Haag

- Ferens, Hull

- Crescent Arts, Scarborough

- Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool

- Hepworth Wakefield

- Yorkshire Sculpture Park

- Stedelijk, Amsterdam

- Henry Moore Institute

- Louisiana

- SMK Copenhagen

- Yorkshire Sculpture International

- Tate Modern

- Whitworth, Manchester

I wasn't quite sure what this was doing in an exhibition about the Moon, but it was fun to watch. The piece, rotating very fast was lit by LED strobe lights, creating a false sense of movement. It is called October 2015 Horoscope, by Camille Henrot. I suppose the Moon has some astrological meaning . . . thinking about it, the bits at the top were displaying phases of the Moon.

I wasn't quite sure what this was doing in an exhibition about the Moon, but it was fun to watch. The piece, rotating very fast was lit by LED strobe lights, creating a false sense of movement. It is called October 2015 Horoscope, by Camille Henrot. I suppose the Moon has some astrological meaning . . . thinking about it, the bits at the top were displaying phases of the Moon.

The Moon – from Inner Worlds to Outer Space, to 20th January 2019

Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Humlabaek, Denmark

The walk from Humlabaek station (halfway between Copenhagen and Helsingor) and the art gallery has always been one of high expectation. The first time I walked the kilometre or so in this quiet, well-off Danish village, I wondered what to expect. The approach to the gallery belies its size – it’s like a Tardis buried beneath a quiet country cottage. It reminds me of post-WW2 UK radar stations that in the 1950s new Cold War age were buried underground, with an innocent looking bungalow perched at the top of the descending ramp to the inner workings, as if that were some kind of disguise. There was one of these at Bempton, near Scarborough, just a stone’s throw from the sheer cliffs which are home to Gannets, Puffins and all sorts of twitchers’ favourites. I only mention this because as one enters the Louisiana underground maze, one emerges at the other end in a café which directly overlooks the sea – and on the horizon Sweden is visible. It is a wonderful setting.

The Moon exhibition is definitely worth the excursion. I wonder if there has ever been an exhibition which so comprehensively explores our relationship with this enigmatic sphere of mystery (the first grainy picture of its dark side, reproduced in the show was only taken in 1959, by a Russian probe) and charts its often romantic appeal from early times to the present. Arthur C. Clarke speculated on how different our lives would be if there was no moon. Looking at this exhibition one is reminded how, in fact, we are often oblivious to it except when it is used as a kind of prop for earthly imaginings. (I confess, if there were werewolf related images here I missed them.) But the moon, as our closest celestial object does remind us occasionally that our everyday horizons are indeed limited and that we should all look up now and then. Given that over half of the human population now lives in cities, many will no longer see the stars as our ancestors did, so perhaps the moon has a certain function to play here.

There is so much to see in this excellently curated show it almost seems invidious to pick out individual parts, but that’s what a super-talented critic like myself must do. I have to remark at this point that I have nothing against Casper David Friedrich nor Joseph Wright of Derby (although I’ve often wondered what Joseph Wright of say Bradford was famous for), whose moonlit pictures are deservedly on show, but the absence of anything by Atkinson Grimshaw has to be noted here with a Yorkshire lick of shadenfruit. Not all nineteenth century paintings had the moon pouring its eerie light on pre-existing romantic scenes. Grimshaw saw that the moon could add romance to industrial scenes too, if for example, docksides might be classed as romantic, and of course they were, being suggestive of journeys to far-off places. Anyway, not to worry, Grimshaw can hold his own elsewhere.

This exhibition suggests that artistic exploration goes hand-in-hand with technological exploration. The landings on the moon, chiefly in the 1970s coincided with new, mainly American adventures in art – Robert Rauschenberg was an artist in residence with NASA (maybe I should write to Elon Musk or Richard Branson and offer my services) but was he the Right Stuff? The fact is, what NASA was producing was art in itself. An exhibited space suit which might have been worn by the first man on the moon Neil Armstrong (this one does actually have his name on it) easily kicks in to touch anything and everything produced by Antony Gormley (a little word on him later). Seen as a sculpture, as a work of art, this suit tells us all we need to know about the fragility of our condition. I often wondered how they made these suits airtight – I assumed the seams were welded – it turns out they were stitched, with no stitch being permitted if it was longer than 0.07mm in length. There must have been a tailor’s quarter somewhere in Houston, or perhaps some émigré community in New York doing this painstaking needlework. The suit speaks clearly and eloquently about the reality of the moon landings, and I wonder if in a curious way if it was seen as importune to show the famous ‘Earthrise’ photograph which so inspired the almost spiritual remarks those moon-bound astronauts had to say about that sight. Perhaps it was a curatorial judgement that this exhibition should have no images of planet Earth at all (unless I missed them, which is always possible.)

NASA still co-operates with artists. One exhibit, a large scale black and white projection of Jupiter shows its moon Io in orbit, changing shape presumably in rhythm with the gravitational pull of its parent. Io is quite a size, but in the grasp of gravity it is a mere liquid, shape-shifting blob. I wish we had a similar time-lapse sequence of Earth, as it ‘rotates’ around the Sun, and indeed as it is pulled by our own moon (it’s a two way street). I put the word rotates in quotation marks because we don’t really rotate in some perfect circle around the Sun, we follow an ellipse, and inevitably the shape of our little blob will shape shift just as Io does. If we could only capture that image and speed it up a bit, it would make us all scared out of our wits, and I have to say that at the present juncture that would be no bad thing.

On that point, another exhibit which contains video footage of a mountaintop observatory I found particularly repellent. This was an astronomical observatory which had shell holes in its dome and which was an abandoned ruin. It appeared to be somewhere in that extensive region where unbridled Islamification has such a terrifying grip. What a depressing sight. The only reason for attacking an astronomical observatory is the desire that we should all just look shamefacedly at our feet, like some version of original sin. The video went off into other territory, and I don’t know whether it also alluded to how science flourished in the Middle East in earlier centuries when all we westerners were bothered with was Crusading and all that. That’s just the trouble with most artists’ videos: they don’t have Spielberg’s touch and it’s too easy to lose interest. But hey, they’re important statements!

I hope I’ve made my point. This is an exhibition which deserves the widest attention. Unusually for me I’ve posted this review more than two months before it closes.

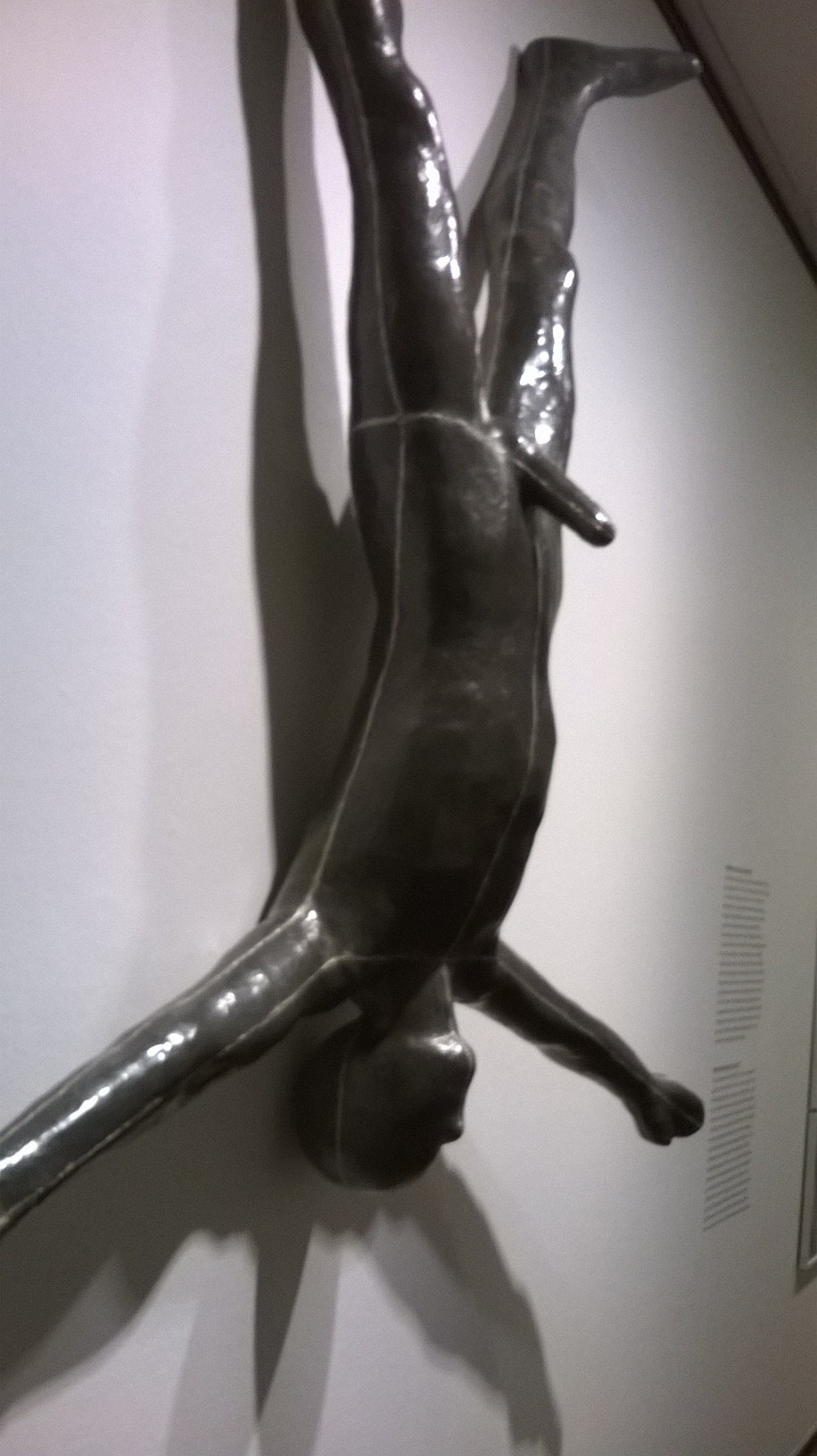

Elsewhere in Louisiana there is loads to see, but I said I would quickly mention Antony Gormley. He has a piece in their permanent collection, which is currently on show. In answer to all those of you who have written in asking how it was he got his knighthood, the answer is here (see below), and well deserved it is too. The piece is well hung albeit accidentally upside down. It’s possible the staff had a problem getting it up. Like I said, I’m a super-talented critic.

Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Humlabaek, Denmark

The walk from Humlabaek station (halfway between Copenhagen and Helsingor) and the art gallery has always been one of high expectation. The first time I walked the kilometre or so in this quiet, well-off Danish village, I wondered what to expect. The approach to the gallery belies its size – it’s like a Tardis buried beneath a quiet country cottage. It reminds me of post-WW2 UK radar stations that in the 1950s new Cold War age were buried underground, with an innocent looking bungalow perched at the top of the descending ramp to the inner workings, as if that were some kind of disguise. There was one of these at Bempton, near Scarborough, just a stone’s throw from the sheer cliffs which are home to Gannets, Puffins and all sorts of twitchers’ favourites. I only mention this because as one enters the Louisiana underground maze, one emerges at the other end in a café which directly overlooks the sea – and on the horizon Sweden is visible. It is a wonderful setting.

The Moon exhibition is definitely worth the excursion. I wonder if there has ever been an exhibition which so comprehensively explores our relationship with this enigmatic sphere of mystery (the first grainy picture of its dark side, reproduced in the show was only taken in 1959, by a Russian probe) and charts its often romantic appeal from early times to the present. Arthur C. Clarke speculated on how different our lives would be if there was no moon. Looking at this exhibition one is reminded how, in fact, we are often oblivious to it except when it is used as a kind of prop for earthly imaginings. (I confess, if there were werewolf related images here I missed them.) But the moon, as our closest celestial object does remind us occasionally that our everyday horizons are indeed limited and that we should all look up now and then. Given that over half of the human population now lives in cities, many will no longer see the stars as our ancestors did, so perhaps the moon has a certain function to play here.

There is so much to see in this excellently curated show it almost seems invidious to pick out individual parts, but that’s what a super-talented critic like myself must do. I have to remark at this point that I have nothing against Casper David Friedrich nor Joseph Wright of Derby (although I’ve often wondered what Joseph Wright of say Bradford was famous for), whose moonlit pictures are deservedly on show, but the absence of anything by Atkinson Grimshaw has to be noted here with a Yorkshire lick of shadenfruit. Not all nineteenth century paintings had the moon pouring its eerie light on pre-existing romantic scenes. Grimshaw saw that the moon could add romance to industrial scenes too, if for example, docksides might be classed as romantic, and of course they were, being suggestive of journeys to far-off places. Anyway, not to worry, Grimshaw can hold his own elsewhere.

This exhibition suggests that artistic exploration goes hand-in-hand with technological exploration. The landings on the moon, chiefly in the 1970s coincided with new, mainly American adventures in art – Robert Rauschenberg was an artist in residence with NASA (maybe I should write to Elon Musk or Richard Branson and offer my services) but was he the Right Stuff? The fact is, what NASA was producing was art in itself. An exhibited space suit which might have been worn by the first man on the moon Neil Armstrong (this one does actually have his name on it) easily kicks in to touch anything and everything produced by Antony Gormley (a little word on him later). Seen as a sculpture, as a work of art, this suit tells us all we need to know about the fragility of our condition. I often wondered how they made these suits airtight – I assumed the seams were welded – it turns out they were stitched, with no stitch being permitted if it was longer than 0.07mm in length. There must have been a tailor’s quarter somewhere in Houston, or perhaps some émigré community in New York doing this painstaking needlework. The suit speaks clearly and eloquently about the reality of the moon landings, and I wonder if in a curious way if it was seen as importune to show the famous ‘Earthrise’ photograph which so inspired the almost spiritual remarks those moon-bound astronauts had to say about that sight. Perhaps it was a curatorial judgement that this exhibition should have no images of planet Earth at all (unless I missed them, which is always possible.)

NASA still co-operates with artists. One exhibit, a large scale black and white projection of Jupiter shows its moon Io in orbit, changing shape presumably in rhythm with the gravitational pull of its parent. Io is quite a size, but in the grasp of gravity it is a mere liquid, shape-shifting blob. I wish we had a similar time-lapse sequence of Earth, as it ‘rotates’ around the Sun, and indeed as it is pulled by our own moon (it’s a two way street). I put the word rotates in quotation marks because we don’t really rotate in some perfect circle around the Sun, we follow an ellipse, and inevitably the shape of our little blob will shape shift just as Io does. If we could only capture that image and speed it up a bit, it would make us all scared out of our wits, and I have to say that at the present juncture that would be no bad thing.

On that point, another exhibit which contains video footage of a mountaintop observatory I found particularly repellent. This was an astronomical observatory which had shell holes in its dome and which was an abandoned ruin. It appeared to be somewhere in that extensive region where unbridled Islamification has such a terrifying grip. What a depressing sight. The only reason for attacking an astronomical observatory is the desire that we should all just look shamefacedly at our feet, like some version of original sin. The video went off into other territory, and I don’t know whether it also alluded to how science flourished in the Middle East in earlier centuries when all we westerners were bothered with was Crusading and all that. That’s just the trouble with most artists’ videos: they don’t have Spielberg’s touch and it’s too easy to lose interest. But hey, they’re important statements!

I hope I’ve made my point. This is an exhibition which deserves the widest attention. Unusually for me I’ve posted this review more than two months before it closes.

Elsewhere in Louisiana there is loads to see, but I said I would quickly mention Antony Gormley. He has a piece in their permanent collection, which is currently on show. In answer to all those of you who have written in asking how it was he got his knighthood, the answer is here (see below), and well deserved it is too. The piece is well hung albeit accidentally upside down. It’s possible the staff had a problem getting it up. Like I said, I’m a super-talented critic.