- About

- Contact

- Blog

- CONSUME

- GALLERY

-

PERAMBULATIONS, Etc.

- Old Parcels Office, Scarborough

- Ghent

- White Cube

- Cornerhouse, Manchester

- Venice 2019

- Tectonics

- Leeds City Art Gallery

- Hayward Gallery, London

- Hull University Art Gallery

- Whitney Gallery, New York

- Royal Scottish Academy, Edinburgh

- Talbot Rice Gallery, Edinburgh

- Fruitmarket Gallery, Edinburgh

- Modern One & Two, Edinburgh

- Groeningemuseum, Bruges

- Humber Street Gallery, Hull

- Renwick Gallery, Washington DC

- Arenthuis, Bruges

- Ropewalk Gallery, Barton on Humber

- Geementmuseum, Den Haag

- Ferens, Hull

- Crescent Arts, Scarborough

- Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool

- Hepworth Wakefield

- Yorkshire Sculpture Park

- Stedelijk, Amsterdam

- Henry Moore Institute

- Louisiana

- SMK Copenhagen

- Yorkshire Sculpture International

- Tate Modern

- Whitworth, Manchester

David Lynch

My head is disconnected

Home, Manchester,

to 29th September 2019

What makes Lynch weird? Could it be his accentuation of the quotidian banality of existence? Certainly, in his films I think he has cornered the market for the strangely familiar, observed from perhaps just two or three degrees outside the normal. In his painting he faces competition. Weird artworks these days barely raise an eyebrow, indeed there’s a post-modern anything goes contest to explore every recess of the mind or the anus, whatever. In this regard, a repeated Lynch motif of human characters appearing to be in the act of vomiting must be a bit passé. But this survey of his work merits our attention for its ability to evoke a sense of latent madness in that aforementioned quotidian banality. One can imagine how this can be achieved in the titles. Ricky discovered his brain was shit barely needs further explanation, but Lynch gives you the whole picture.

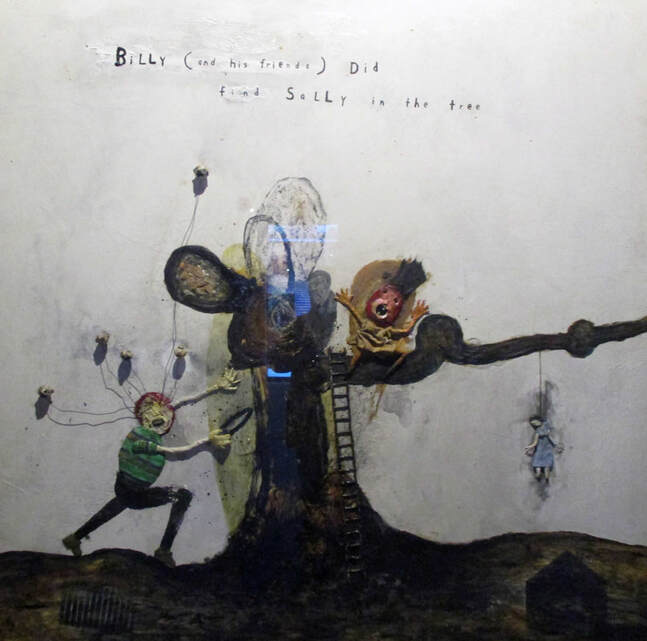

The words Lynch employs in many of these works capture a certain existential angst. A lonely figure talks to himself softly. Where are you going you fucking idiot? has a suggestive Munch Scream-like quality. Billy (and his friends) did find Sally in the tree finds Sally hanging inert from a branch, in what has a feel for a scene from Goya’s Disasters of War. Lynch’s tree has only one long, abnormal branch and appears to serve only one predetermined purpose. There’s no knowing what the circumstances were of Sally’s hanging, but the tree is clearly complicit. Billy (and his friends) won’t save Sally from the tree’s clutches. Maybe she doesn’t want saving and perhaps she was so sick of Billy’s useless ways she did indeed decide to top herself.

This is one of the qualities I like about Lynch’s work, its storytelling. Most of the pictures contain short sentences which he then dissects or visually examines in absurdist fashion. Mind you, if you told yourself that your brain was shit, it does conjure up a particular image. The language is also slightly odd. In the case of Billy and Sally, why not simply say Billy . . . found Sally in the tree? There’s a hint of something biblical about the language, suggestive of parables. Are these pictures parables, do they actually contain moral content? I’ll have to watch Eraserhead again to find the inner Lynch. On the other hand, perhaps the grammar is a kind of American form, a characteristic of the tortured souls he portrays, those who may have flocked to hear Elmer Gantry in the 1930s.

Much of the work is very material. His large mixed media pictures, rather sumptuously framed in modern gilt frames are thick with texture and some could be described as part painting, part sculpture in a manner which could have been current nearly 100 years ago. Some have dull, glowing light bulbs, lumps of indistinct deposits, wire and detritus. There’s always more room for this combination in my book. An early series of pictures are Lynch’s equivalent of the miniature – drawings made in the interior of used matchbooks. The stumps of the matches are like rows of decapitated teeth – not rotten since they are broken off in their prime, as it were. The idiom of collected matchbooks suggests an acquisitive mentality. One can imagine Lynch eyeing some vision or other as he draws on his fag (no pun intended) and mentally exudes absurdities even as he exhales. His heavily lived-in face, seen on posters around the city centre suggests he’s had quite a few absurdist exhalations.